The Farnsworth House was designed and completed from 1946 to 1951 and is considered a prominent icon of Modern Architecture in America. It was Mies Van der Rohe’s first completed domestic project although it unapologetically breaks all the rules of domesticity.

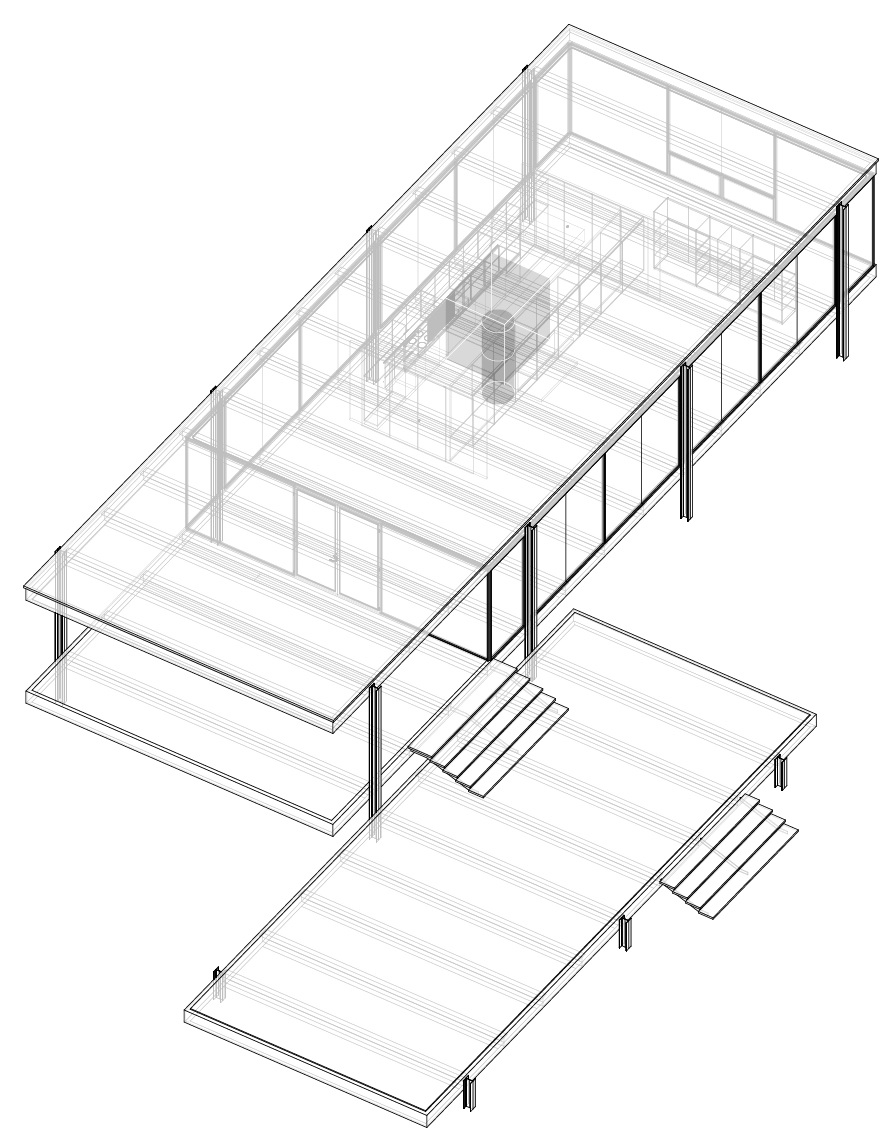

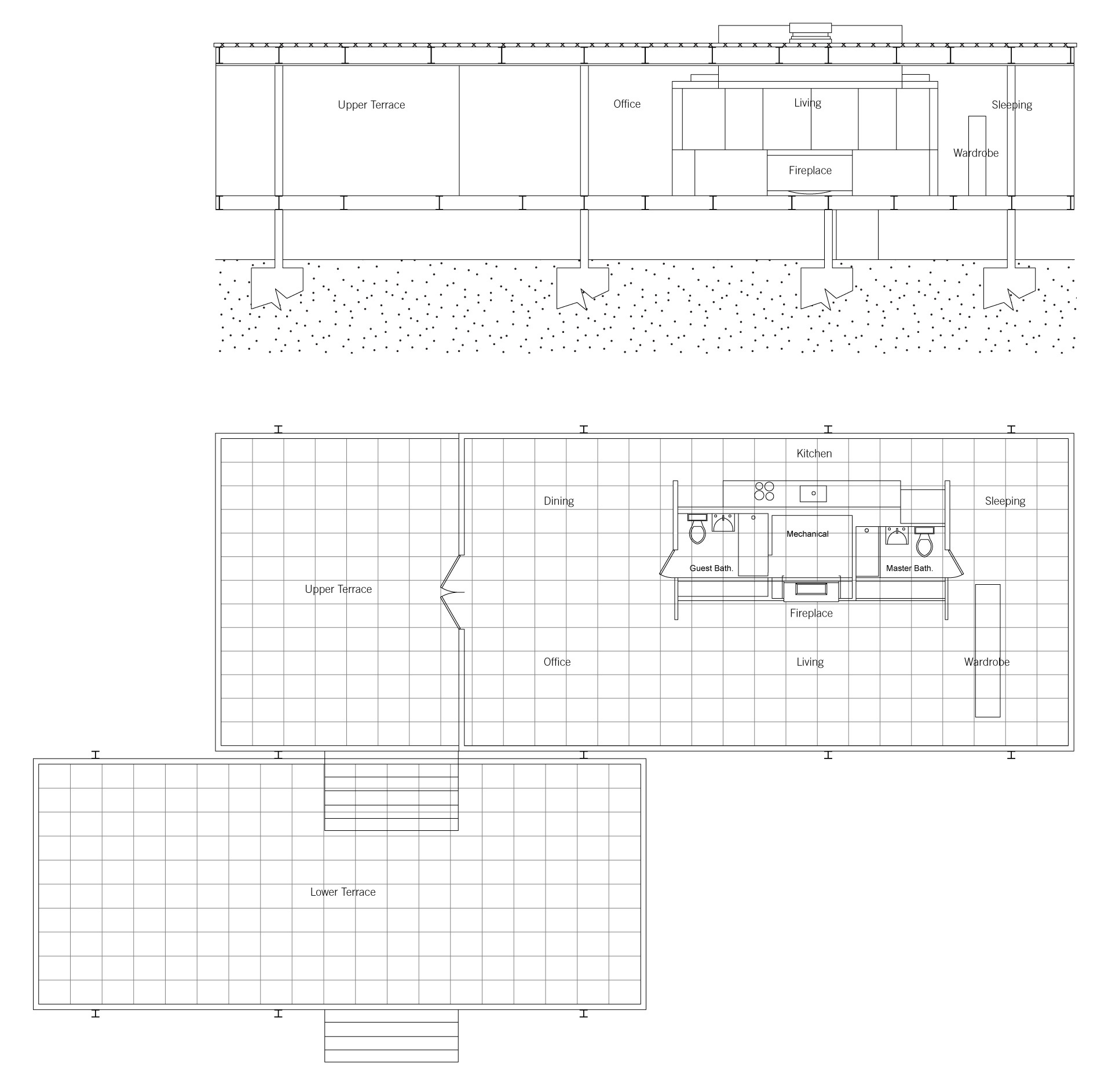

The house consists of two rectangular slabs floating above the ground. Stairs connect the ground to the terrace slab, which connects to the main house slab which doubles as the exterior deck space as well as interior floor.

The house consists of two rectangular slabs floating above the ground. Stairs connect the ground to the terrace slab, which connects to the main house slab which doubles as the exterior deck space as well as interior floor.

Although the house is an ultimate example of ‘skin-and-bone’ architecture, its heart still beats from within the asymmetrically located core, a volume continging the kitchen, bathroom and fireplace. Unlike the rest of the house, composed of steel and glass, the core is constructed with primavera plywood and is the only place where elements puncture the roof and floor planes. Drain and sewage pipes through the floor to the ground, and a vertical shaft containing the bathroom vents and the fireplace puncture the roof. These utilities are hidden within the inaccessible centers of the slabs, making them invisible from any view.

Site / Buffer / Negative Interiority (Left)

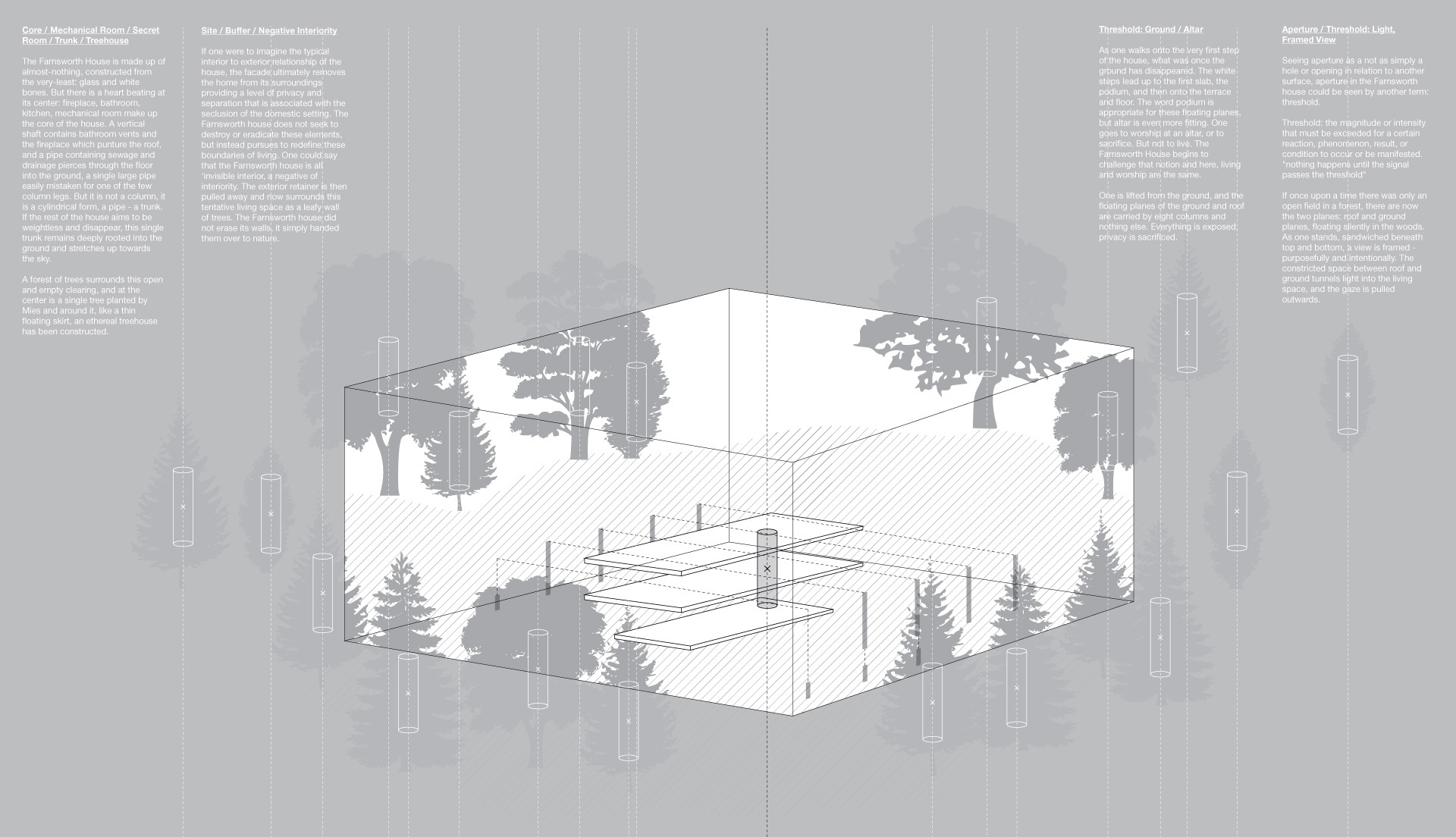

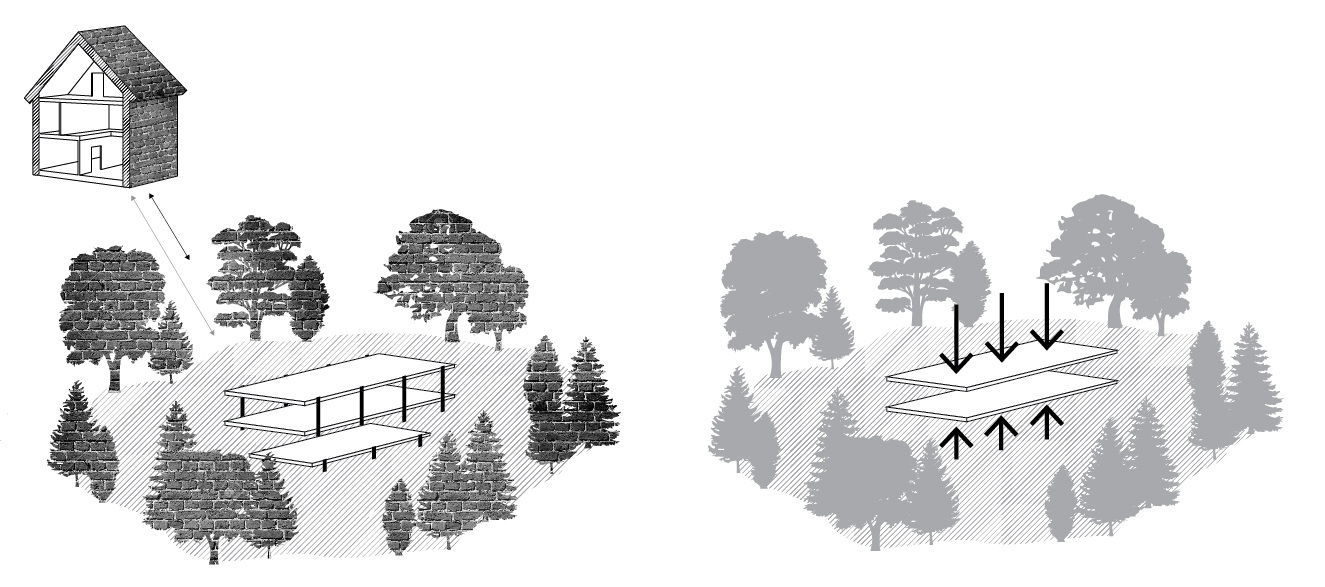

If one were to imagine the typical interior to exterior relationship of the house, the facade ultimately removes the home from its surroundings providing a level of privacy and separation that is associated with the seclusion of the domestic setting. The Farnsworth house does not seek to destroy or eradicate these elements, but instead pursues to redefine these boundaries of living. One could say that the Farnsworth house is all ‘invisible interior, a negative of interiority. The exterior retainer is then pulled away and now surrounds this tentative living space as a leafy wall of trees. The Farnsworth house did not erase its walls, it simply handed them over to nature.

If one were to imagine the typical interior to exterior relationship of the house, the facade ultimately removes the home from its surroundings providing a level of privacy and separation that is associated with the seclusion of the domestic setting. The Farnsworth house does not seek to destroy or eradicate these elements, but instead pursues to redefine these boundaries of living. One could say that the Farnsworth house is all ‘invisible interior, a negative of interiority. The exterior retainer is then pulled away and now surrounds this tentative living space as a leafy wall of trees. The Farnsworth house did not erase its walls, it simply handed them over to nature.

Aperture / Threshold: Light, Framed View (Right)

Seeing aperture as a not as simply a hole or opening in relation to another surface, aperture in the Farnsworth house could be seen by another term: threshold. [Threshold: the magnitude or intensity that must be exceeded for a certain reaction, phenomenon, result, or condition to occur or be manifested.“nothing happens until the signal passes the threshold”] If once upon a time there was only an open field in a forest, there are now the two planes: roof and ground planes, floating silently in the woods. As one stands, sandwiched beneath top and bottom, a view is framed - purposefully and intentionally. The constricted space between roof and ground tunnels light into the living space, and the gaze is pulled outwards.

Seeing aperture as a not as simply a hole or opening in relation to another surface, aperture in the Farnsworth house could be seen by another term: threshold. [Threshold: the magnitude or intensity that must be exceeded for a certain reaction, phenomenon, result, or condition to occur or be manifested.“nothing happens until the signal passes the threshold”] If once upon a time there was only an open field in a forest, there are now the two planes: roof and ground planes, floating silently in the woods. As one stands, sandwiched beneath top and bottom, a view is framed - purposefully and intentionally. The constricted space between roof and ground tunnels light into the living space, and the gaze is pulled outwards.

Threshold: Ground / Altar (Left)

As one walks onto the very first step of the house, what was once the ground has disappeared. The white steps lead up to the first slab, the podium, and then onto the terrace and floor. The word podium is appropriate for these floating planes, but altar is even more fitting. One goes to worship at an altar, or to sacrifice. But not to live. The Farnsworth House begins to challenge that notion and here, living and worship are the same. One is lifted from the ground, and the floating planes of the ground and roof are carried by eight columns and nothing else. Everything is exposed, privacy is sacrificed.

As one walks onto the very first step of the house, what was once the ground has disappeared. The white steps lead up to the first slab, the podium, and then onto the terrace and floor. The word podium is appropriate for these floating planes, but altar is even more fitting. One goes to worship at an altar, or to sacrifice. But not to live. The Farnsworth House begins to challenge that notion and here, living and worship are the same. One is lifted from the ground, and the floating planes of the ground and roof are carried by eight columns and nothing else. Everything is exposed, privacy is sacrificed.

Core / Mechanical Room / Secret Room / Trunk / Treehouse (Right)

The Farnsworth House is made up of almost-nothing, constructed from the very-least: glass and white bones. But there is a heart beating at its center: fireplace, bathroom, kitchen, mechanical room make up the core of the house. A vertical shaft contains bathroom vents and the fireplace which punture the roof, and a pipe containing sewage and drainage pierces through the floor into the ground, a single large pipe easily mistaken for one of the few column legs. But it is not a column, it is a cylindrical form, a pipe - a trunk. If the rest of the house aims to be weightless and disappear, this single trunk remains deeply rooted into the ground and stretches up towards the sky. A forest of trees surrounds this open and empty clearing, and at the center is a single tree planted by Mies and around it, like a thin floating skirt, an ethereal treehouse has been constructed.

The Farnsworth House is made up of almost-nothing, constructed from the very-least: glass and white bones. But there is a heart beating at its center: fireplace, bathroom, kitchen, mechanical room make up the core of the house. A vertical shaft contains bathroom vents and the fireplace which punture the roof, and a pipe containing sewage and drainage pierces through the floor into the ground, a single large pipe easily mistaken for one of the few column legs. But it is not a column, it is a cylindrical form, a pipe - a trunk. If the rest of the house aims to be weightless and disappear, this single trunk remains deeply rooted into the ground and stretches up towards the sky. A forest of trees surrounds this open and empty clearing, and at the center is a single tree planted by Mies and around it, like a thin floating skirt, an ethereal treehouse has been constructed.

The entry platform slides past the base of the house as a flat plane that is carried on six columns in opposition to the larger volume carried on eight. The two symmetrical elements are asymmetrically overlapped. Kenneth Frampton describes this move as the ‘elevation of a house to the status of monument’. The podium, the steps, the terrace and the floor are all lifted and produce a new ground condition.

If an aperture is defined as a hole or opening through which light travels then the Farnsworth House is ultimately made up of frail limbs and the light that fills the space between them. The facade is made up of 1/4” thick single-pane clear glass panels spanning 9’-6” from floor to ceiling. This fully transparent facade aims to blur the boundary between outside and inside, an invisible box that is the resultant of what Mies’s called beinahe nichts, ‘almost nothing’.

The major slabs of material (podium, steps, terrace, and floor) are made of travertine, a white limestone. The exposed steel work was sprayed white after having been ground down to remove all the welds. The whiteness of the material renders it a non-material, removing its visual presence. The steel skeletal frame structure of the house supports the roof and floor planes without every piercing or penetrating through them, as if the planes were trapped mid-flight between the column structure. refusing to be grounded in any sort of tectonic give-away.

The major slabs of material (podium, steps, terrace, and floor) are made of travertine, a white limestone. The exposed steel work was sprayed white after having been ground down to remove all the welds. The whiteness of the material renders it a non-material, removing its visual presence. The steel skeletal frame structure of the house supports the roof and floor planes without every piercing or penetrating through them, as if the planes were trapped mid-flight between the column structure. refusing to be grounded in any sort of tectonic give-away.