Undergraduate Thesis

April 2017

Advisor: Marcelo Spina

AT: Zaid Kashef Alghata

Special Thesis Advisor: Wolf D. Prix

April 2017

Advisor: Marcelo Spina

AT: Zaid Kashef Alghata

Special Thesis Advisor: Wolf D. Prix

Awarded Undergraduate Thesis Prize

Selected for AIA LA 2x8 Exhibition 2017

Featured in Undergraduate Thesis Exhibition 2017

Part of SCI-Arc Spring Show 2017

Selected for AIA LA 2x8 Exhibition 2017

Featured in Undergraduate Thesis Exhibition 2017

Part of SCI-Arc Spring Show 2017

Special thanks to: Nancy Ai, Meenakshi Dravid, Meghan Hui, Christopher Jimenez, Graham Jordan, Johan Wijesinghe, James Li, Alejandro Loor

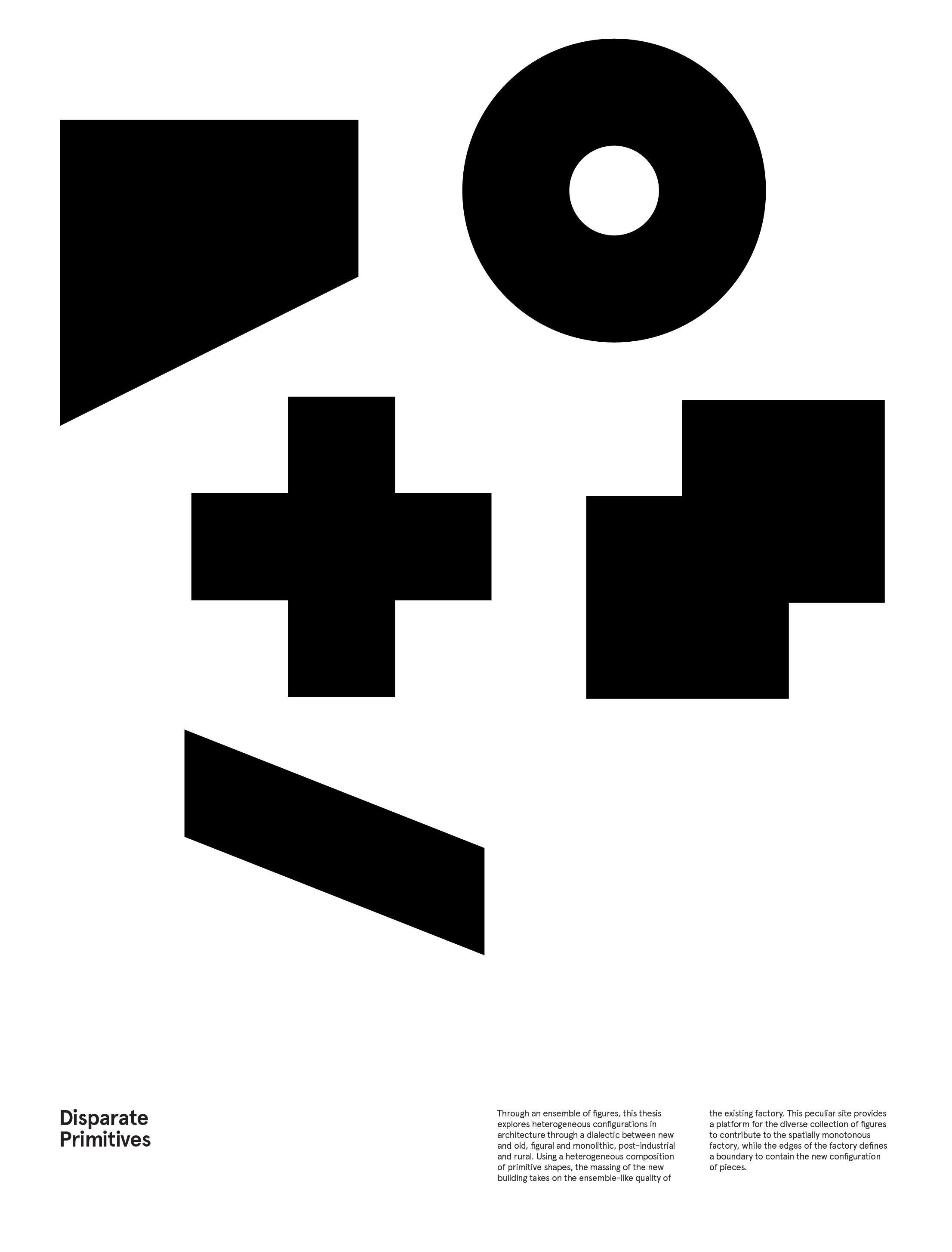

Through an ensemble of figures, this thesis explores heterogeneous configurations in architecture through a dialectic between new and old, figural and monolithic, post-industrial and rural.

Located on the outskirts of Bologna, this project sits atop an existing factory with expressive structure reminiscent of Nervi’s Paper Factory in Mantua. The use of primitives provides a diverse collection of figures to contribute to the heavily grided, spatially monotonous factory, while the edges of the factory building define a boundary to contain the new configuration of pieces. Through an estrangement of these elements, this building takes on the town’s post-industrial state of atrophy and hopes to revitalize it with a renewed relevance.

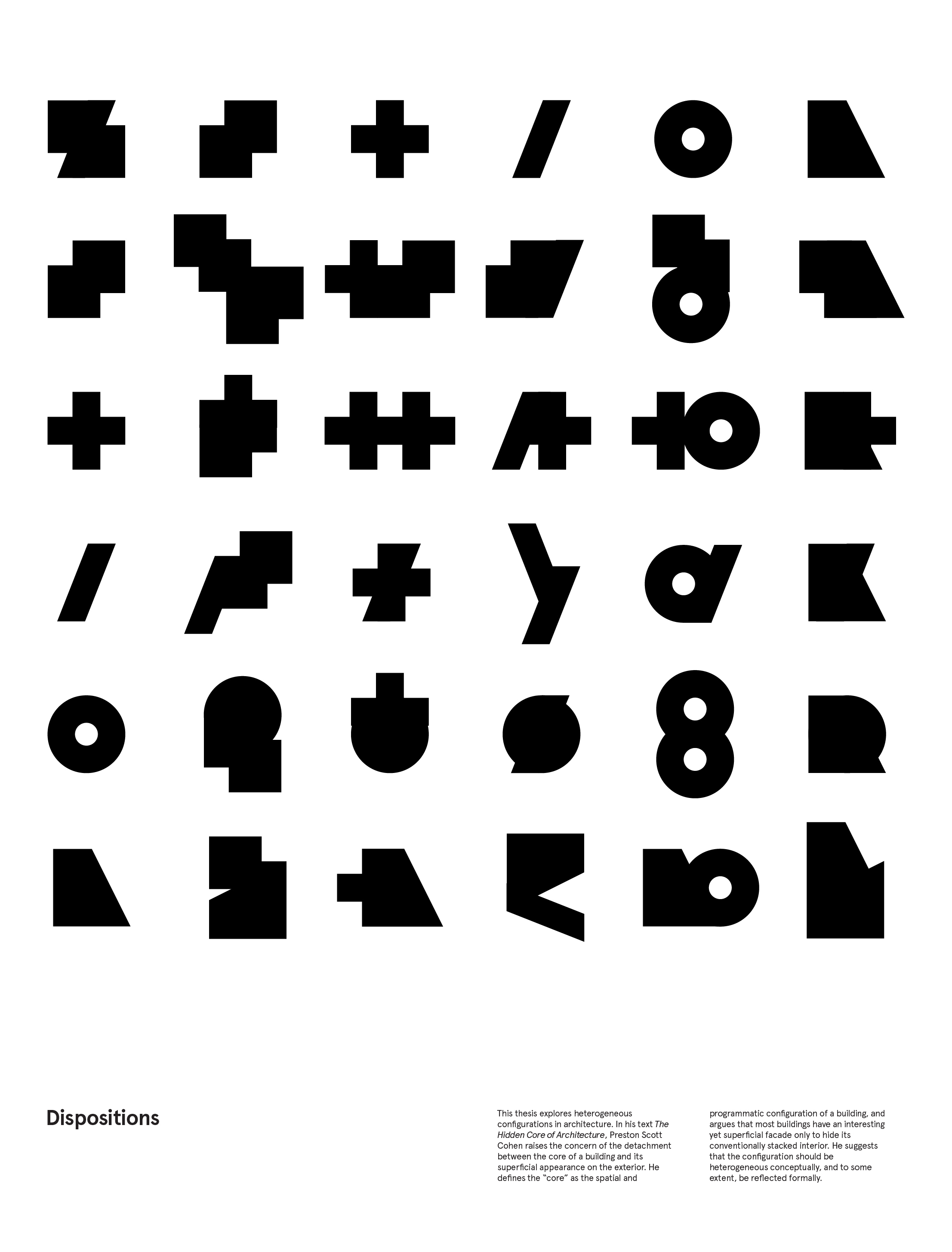

In his text The Hidden Core of Architecture, Preston Scott Cohen raises the concern of the detachment between the core of a building and its superficial appearance on the exterior.

Located on the outskirts of Bologna, this project sits atop an existing factory with expressive structure reminiscent of Nervi’s Paper Factory in Mantua. The use of primitives provides a diverse collection of figures to contribute to the heavily grided, spatially monotonous factory, while the edges of the factory building define a boundary to contain the new configuration of pieces. Through an estrangement of these elements, this building takes on the town’s post-industrial state of atrophy and hopes to revitalize it with a renewed relevance.

In his text The Hidden Core of Architecture, Preston Scott Cohen raises the concern of the detachment between the core of a building and its superficial appearance on the exterior.

He defines the “core” as the internal spatial and programmatic configuration of a building. He argues that most buildings have interesting yet superficial facades only to hide their conventional stacked interior floors. He suggests that the configuration should be

conceptually

heterogeneous, and to some extent, be reflected formally.

When summarizing his essay, Scott Cohen reiterates that “only the architecture that transforms the hidden core, the part that enables the impermanent parts to change perpetually, can alter the balance between endurance and impermanence, effect the architectural space in which we live, and go on mattering indefinitely.”

However, as the configuration of the core becomes more dynamic and spatially diverse, the problem continues to exist. This is because the exterior, if it remains static, will now become a monolithic veil that hides its heterogeneous interior. Morphosis’ Emerson College begins to answer this problem by liberating its core through partially exposing it.

When summarizing his essay, Scott Cohen reiterates that “only the architecture that transforms the hidden core, the part that enables the impermanent parts to change perpetually, can alter the balance between endurance and impermanence, effect the architectural space in which we live, and go on mattering indefinitely.”

However, as the configuration of the core becomes more dynamic and spatially diverse, the problem continues to exist. This is because the exterior, if it remains static, will now become a monolithic veil that hides its heterogeneous interior. Morphosis’ Emerson College begins to answer this problem by liberating its core through partially exposing it.

The issue of core in Scott Cohen’s writing signifies beyond the literal meaning of an elevator-mechanical core. He argues buildings that utilize “computation and its generation of surfaces has done little more than produce a new style for cladding the core structure of buildings, thereby maintaining modern architecture’s spatial status quo” and because of that, “the part of the building that is relatively permanent - the core frame, floors, circulation and vertical air shafts — is largely ignored.”

In Morphosis’ Emerson College’s sectional drawing, the core becomes autonomous and is partially exposed, while still remains within the building. It begins to break away from the inversed relationship of having its “interesting core” being veiled by a “boring exterior”. Emerson College appears to be tackling the issue, although it is still apparent that its core in certain views are being hidden by a monolithic box. Departing from this trajectory, there is perhaps a need to call for a configuration that is completely liberated. A building without an exterior seemingly concealing its interior; nor an interior more spatially aware than its straightforwardly designed skin.

Continuing the trajectory, this project attempts to answer the question with heterogeneously configured parts that are completely “liberated”.

Continuing the trajectory, this project attempts to answer the question with heterogeneously configured parts that are completely “liberated”.

As a recycling museum and green academy, this project is situated on the edge of a heavily industrialized area while adjacent to a national park. This project attempts to mediate the two languages through form and program at different scales. Using a composition of primitive shapes, the massing of the new building takes on the pack-and-stacked quality of the existing factory and its context, and expresses it elevationally. The pieces are composed of both familiar and foreign elements: abrupt piling of found shapes within the factory complex, allusion to the pitch of a vernacular sawtooth factory roof, or the abstraction of the forest through etched-metal panels.

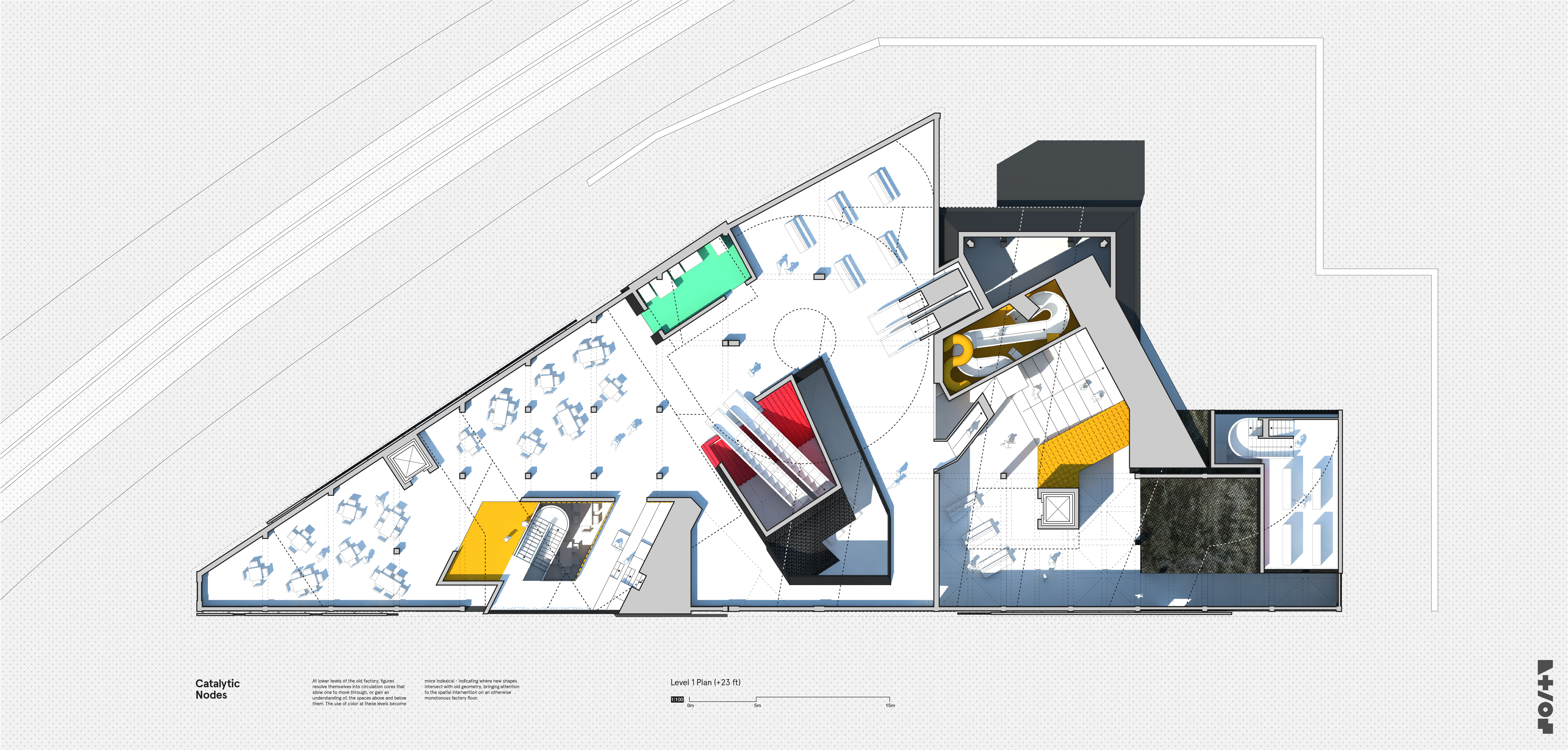

At lower levels of the old factory, figures resolve themselves into circulation cores that allow one to move through, or gain an understanding of, the spaces above and below them. The use of color at these levels are more indexical - indicating where new shapes intersect with old geometry.

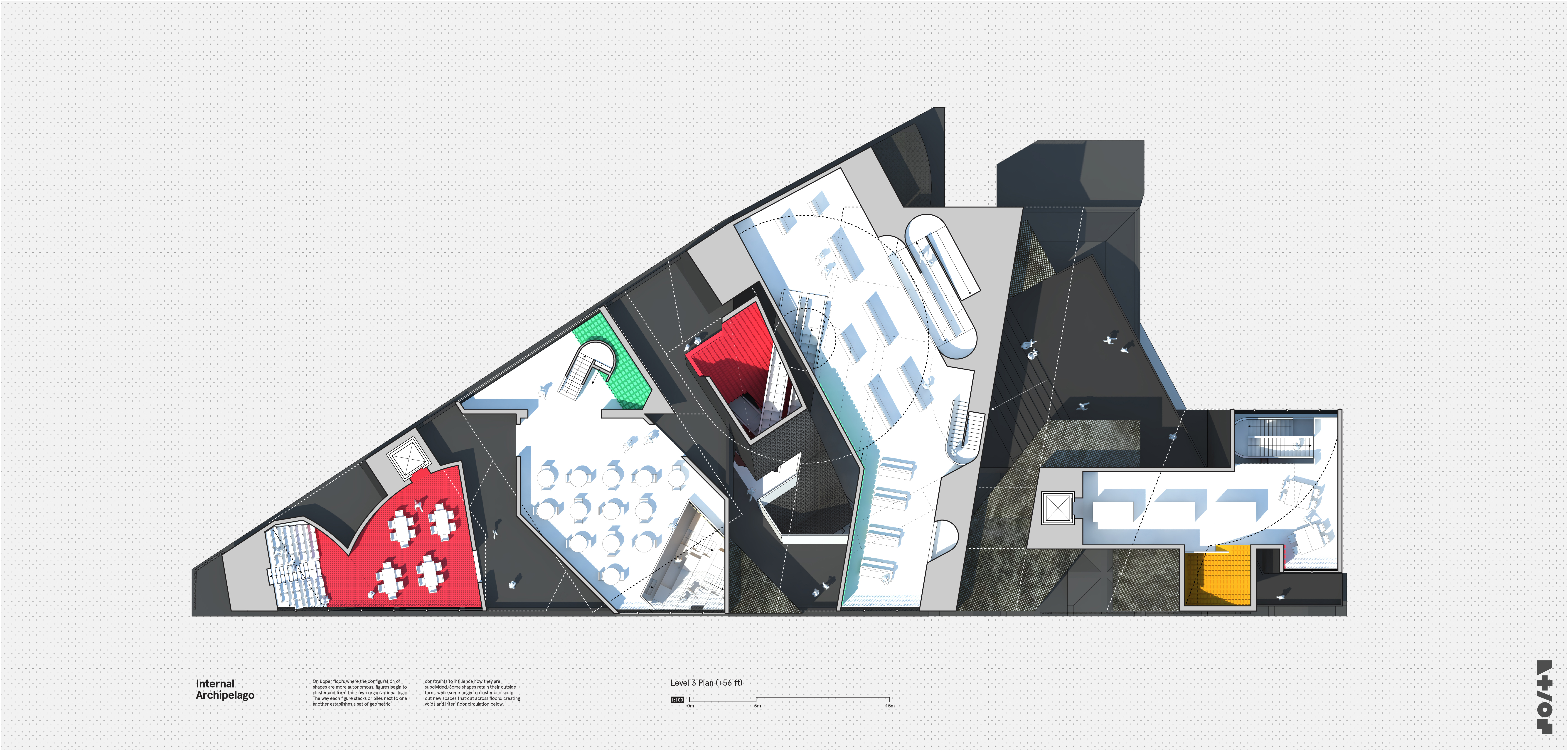

Inside, the new form begins to interact with the old factory through various methods of resolution. Some figures retain their outside form, while some begin to cluster and sculpt out new spaces that cut across floors, creating voids and inter-floor circulation.

On upper floors where the configuration of shapes are more autonomous, figures begin to cluster and form their own organizational logic. The way each figure stacks or piles next to another establishes a set of geometric constraints to influence how they are divided. Color on these levels become more expressive, highlighting specific surfaces to call out its distinctive geometry in relation to, or distinguish from its exterior.

The langauge of shape to space extends all the way to the building’s envelope. The outline of the configurations are weaved into a metric to form subdivisions on the perforated metal cladding as well as fritting on glass panels.

On upper floors where the configuration of shapes are more autonomous, figures begin to cluster and form their own organizational logic. The way each figure stacks or piles next to another establishes a set of geometric constraints to influence how they are divided. Color on these levels become more expressive, highlighting specific surfaces to call out its distinctive geometry in relation to, or distinguish from its exterior.

The langauge of shape to space extends all the way to the building’s envelope. The outline of the configurations are weaved into a metric to form subdivisions on the perforated metal cladding as well as fritting on glass panels.