Studio

Fall 2019

Instructor: Hillary Sample, Michael Meredith, MOS

Special thanks to Stella Rossikopoulou Pappa

Fall 2019

Instructor: Hillary Sample, Michael Meredith, MOS

Special thanks to Stella Rossikopoulou Pappa

“All studies grow out of relation in the one great common world.”1

In School and Society, John Dewey states that when the child participates in a varied but concrete but active relationship to the common world, their studies are naturally unified and will no longer be a problem to correlate studies. This project proposes the utilization of participation, both physically and intellectually, into the design of the laboratory school of Columbia University in the City of New York. The physical model of the project is both a representation of architectural ideas and a planning apparatus of spatial organization for the users that occupy it.

“In supervised play with precut simple geometrical building blocks, organized into didactic exercises of increasing complexity called gifts, Froebel saw a means of enabling children to perceive a relationship between the whole and part of such structures as a bath, a house, or church and of providing them with an opportunity to use, apply, or modify what they had learned.”2

In School and Society, John Dewey states that when the child participates in a varied but concrete but active relationship to the common world, their studies are naturally unified and will no longer be a problem to correlate studies. This project proposes the utilization of participation, both physically and intellectually, into the design of the laboratory school of Columbia University in the City of New York. The physical model of the project is both a representation of architectural ideas and a planning apparatus of spatial organization for the users that occupy it.

“In supervised play with precut simple geometrical building blocks, organized into didactic exercises of increasing complexity called gifts, Froebel saw a means of enabling children to perceive a relationship between the whole and part of such structures as a bath, a house, or church and of providing them with an opportunity to use, apply, or modify what they had learned.”2

To Friedrich Froebel, the kindergarten is not a place, but a set of objects. This project is interested in the pedagogical idea that the act of learning through participation, i.e. the assembly of construction toy blocks, can inform the design of the building it takes place in. Froebel’s gifts are an abstraction of architectural elements that are simplified and miniaturized for ease of learning. The lineage of construction toys has since evolved and taken numerous iterations: Legos, Tinkertoy, K’Nex, ZOOB Play System…

This project proposes, in the context of building design, a shift from that lineage to re-introduce architectural context into the construction toy. The architect crosses into the realm of toy design by producing a model of the building that is interactive and playable, while its intended occupants—the students and teachers of the laboratory school—gains agency through a clear understanding of the space they occupy and the ability to participate in the design of those spaces.

This project proposes, in the context of building design, a shift from that lineage to re-introduce architectural context into the construction toy. The architect crosses into the realm of toy design by producing a model of the building that is interactive and playable, while its intended occupants—the students and teachers of the laboratory school—gains agency through a clear understanding of the space they occupy and the ability to participate in the design of those spaces.

Playset, situated somewhere between 1:1—1:8” scale

“...these exercises demonstrate a reversal of Winston Churchill’s 1944 argument: we shape our buildings, and afterwards, our buildings shape us”, an architect studying existing structures might suggest that “our buildings shape us and afterwards we shape our buildings.” It is this exchange between model, building, and user that makes the signification, simulation, and projection of architecture possible.”3

The laboratory school as a design project does not only appeal to its imaginary occupants, but also relates to the larger architectural discourse and us—the participants of the studio. The model has played a large role in the history of architecture education, as it is the first materialization of architectural ideas in the physical dimension, and requires a consideration of material tectonics for it to be structurally sound enough to hold its shape, regardless of its intended scale.

The invention of computer-aided design software has altered the nature of physical models today, reducing them to mere objects of final production of little relevance to the design process. Examining so closely at pedagogies and education, this project hopes to bring back the model as a design tool, and further that exploration to utilize the model as a diagram and an instrument of playful experimentation.

The laboratory school as a design project does not only appeal to its imaginary occupants, but also relates to the larger architectural discourse and us—the participants of the studio. The model has played a large role in the history of architecture education, as it is the first materialization of architectural ideas in the physical dimension, and requires a consideration of material tectonics for it to be structurally sound enough to hold its shape, regardless of its intended scale.

The invention of computer-aided design software has altered the nature of physical models today, reducing them to mere objects of final production of little relevance to the design process. Examining so closely at pedagogies and education, this project hopes to bring back the model as a design tool, and further that exploration to utilize the model as a diagram and an instrument of playful experimentation.

This brings us closely to Dewey’s view on education, because “fruitful conceptual-theoretical work needed constant check and interplay with the stuff of the real world”; as well as Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi’s pedagogical theory that a lesson can be successful only when the head, heart and hands of the pupil are spoken to.4 And that learning, more specifically in elementary education, is a process that requires hands-on participation and an understanding across subjects and fields.

“...the study of the fibres, of geographical features, the conditions under which raw materials are grown, the great centres of manufacture and distribution, the physics involved in the machinery of production; [...]. You can concentrate the history of all mankind into the evolution of the flax, cotton, and wool fibres into clothing”5

-John Dewey

Moving from physical participation in the process of design, the pedagogy of the school also incorporates participation in its intellectual sense. On this subject, Dewey states that the learning process should help students understand materials and ideas in the world are interconnected, and “all waste is due to isolation”. That things cannot exist without its participation and relations to other things—be it a dish from its ingredients, or subjects in the classroom from its application at home or the outside world. The design of this project acknowledges this correlation, and addresses this “web of life” concept in its spatial organization.

“...the study of the fibres, of geographical features, the conditions under which raw materials are grown, the great centres of manufacture and distribution, the physics involved in the machinery of production; [...]. You can concentrate the history of all mankind into the evolution of the flax, cotton, and wool fibres into clothing”5

-John Dewey

Moving from physical participation in the process of design, the pedagogy of the school also incorporates participation in its intellectual sense. On this subject, Dewey states that the learning process should help students understand materials and ideas in the world are interconnected, and “all waste is due to isolation”. That things cannot exist without its participation and relations to other things—be it a dish from its ingredients, or subjects in the classroom from its application at home or the outside world. The design of this project acknowledges this correlation, and addresses this “web of life” concept in its spatial organization.

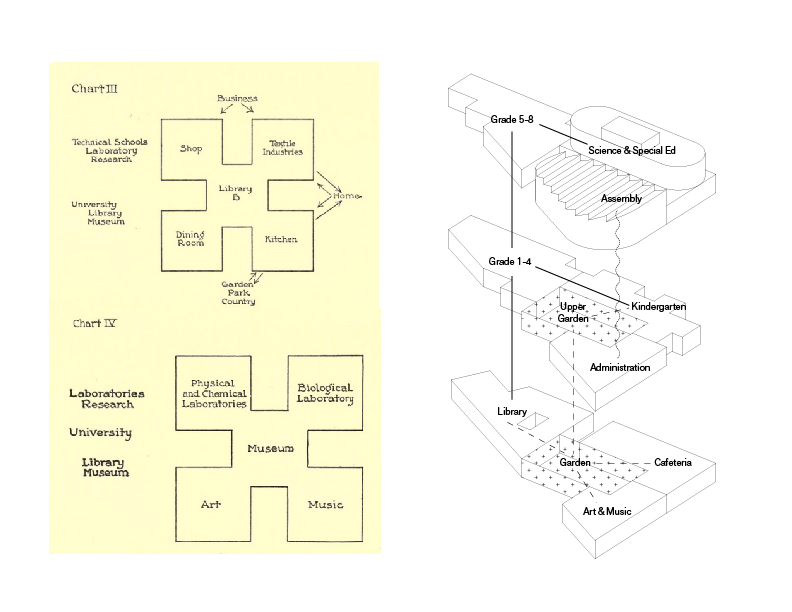

Fig.1&2

︎Precedents

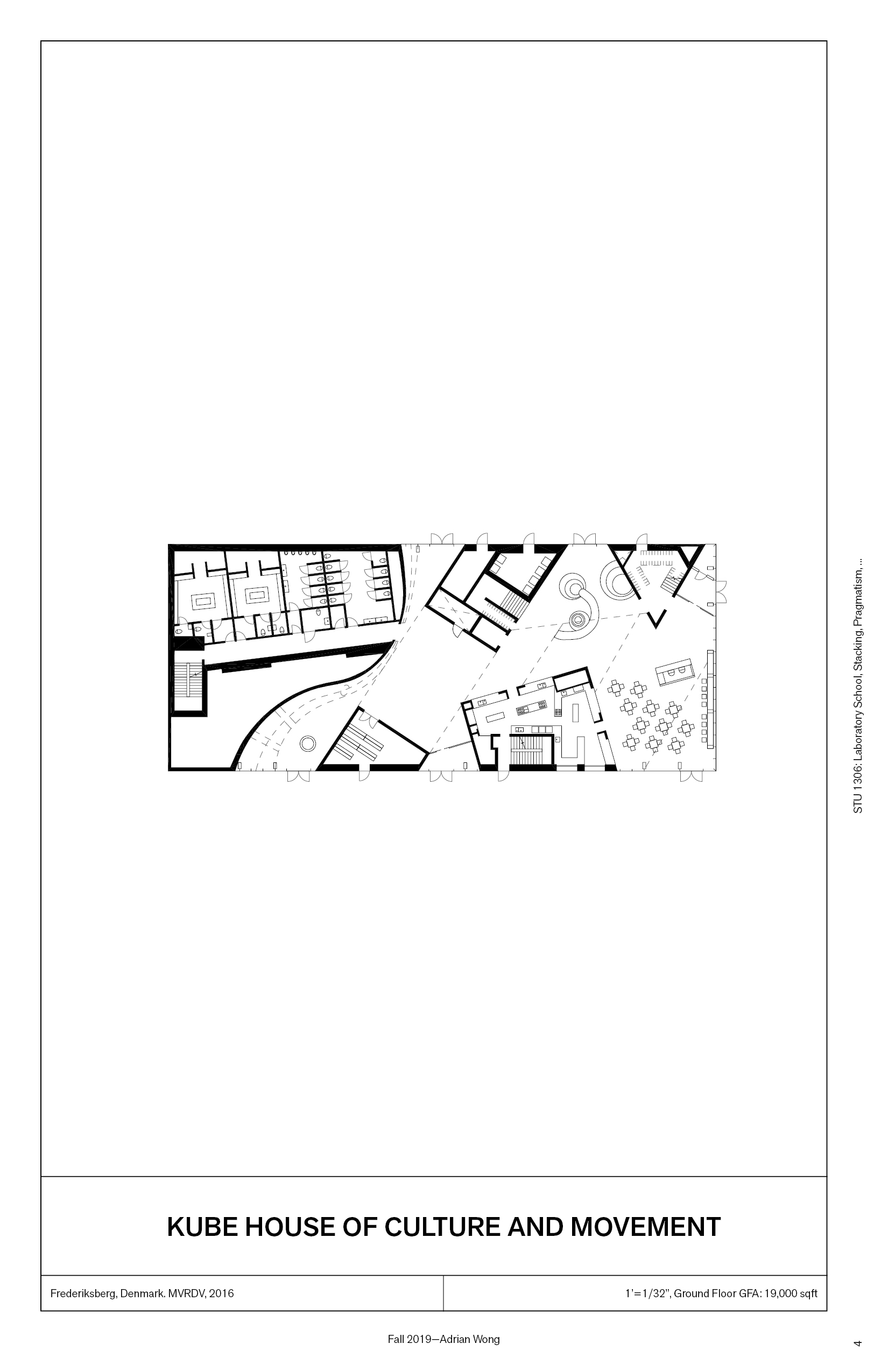

New York City H-Type Public School, 1906

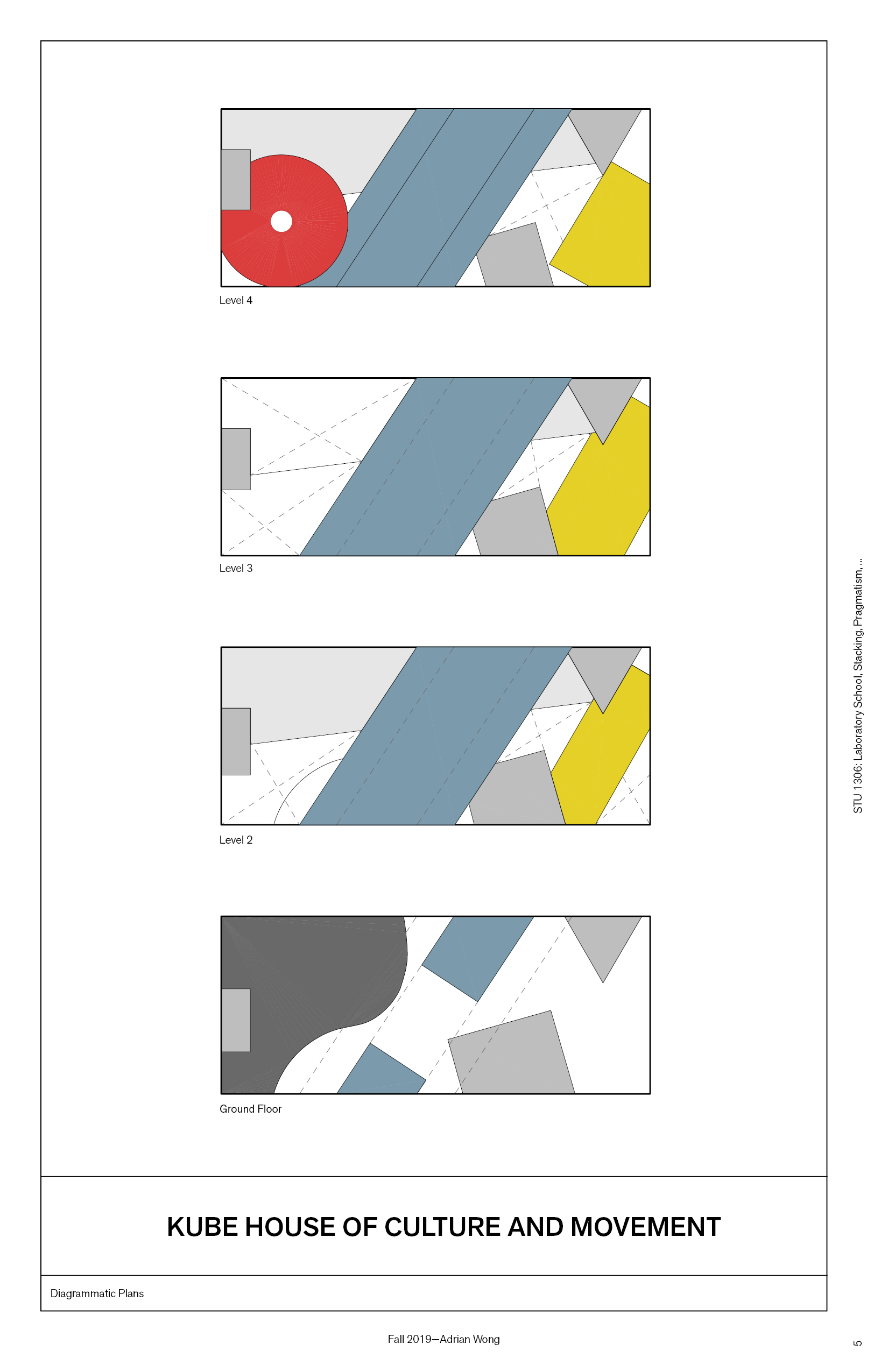

KuBe Community Center, 2016

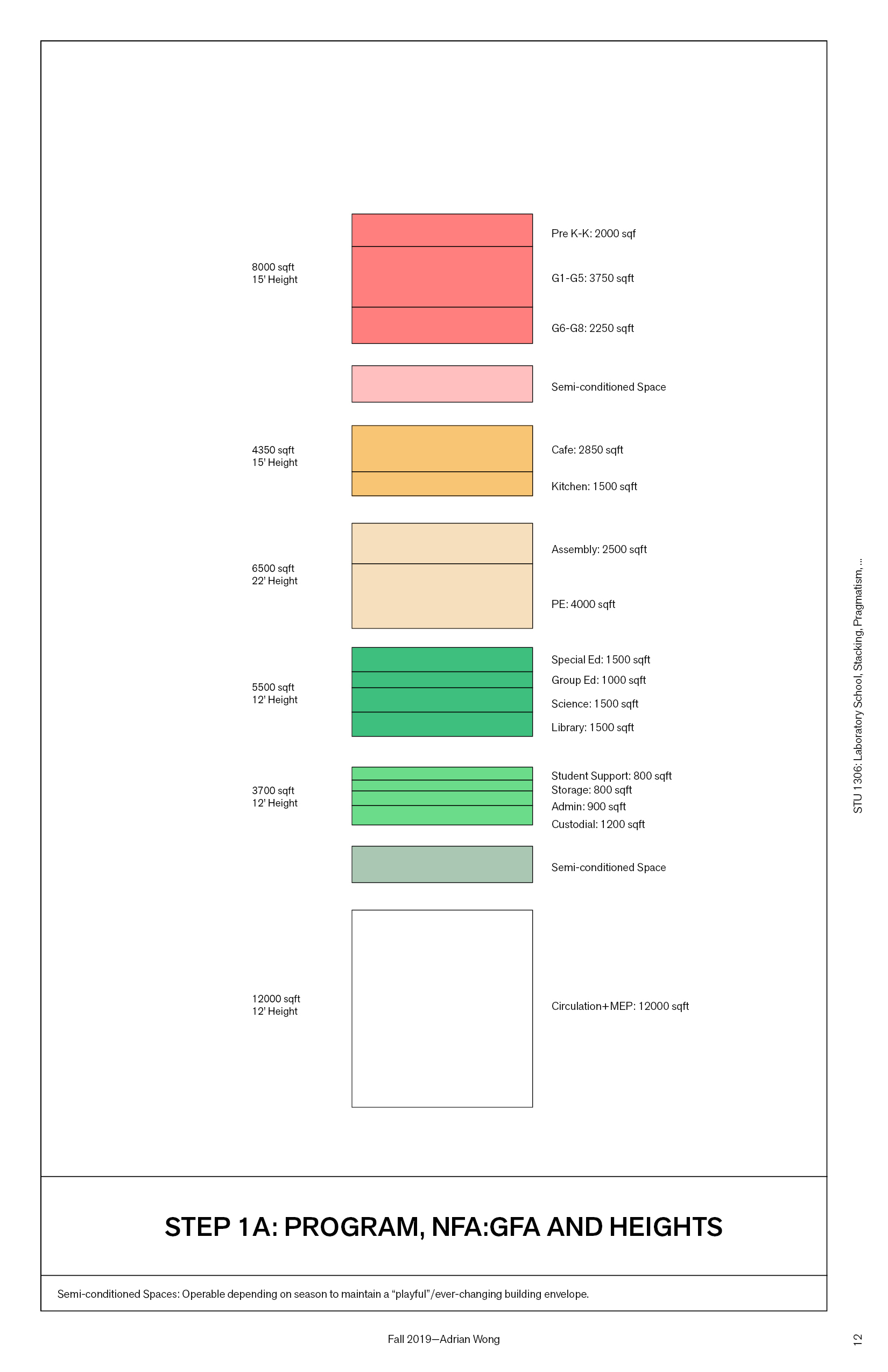

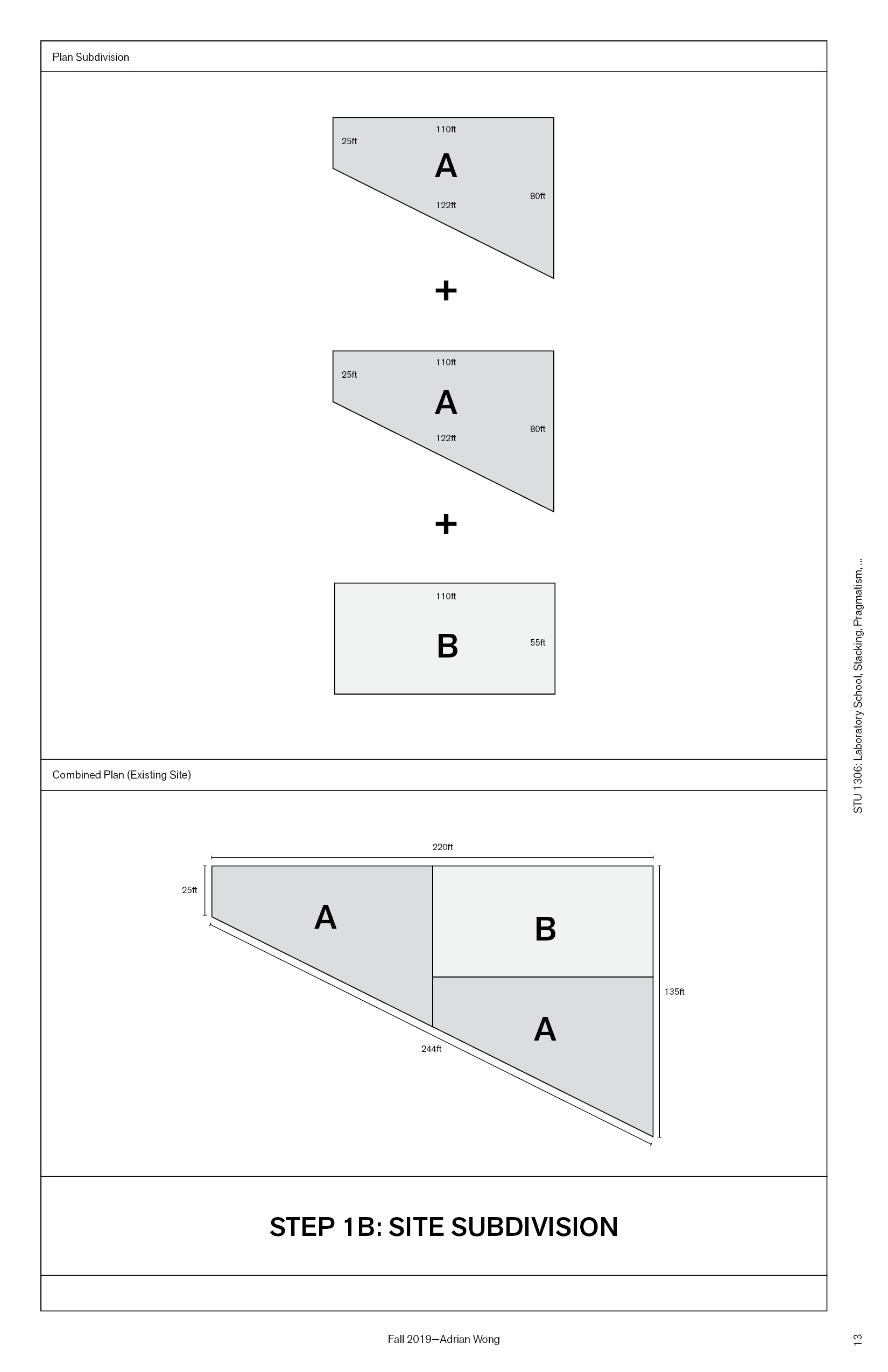

The program arrangement of the laboratory school continues that of Dewey’s in Chicago, but introduces a much more three-dimensional correlation between its parts through stacking. Dewey proposed that the school be surrounded by trees and a garden, where its intimate association with nature would begin. Given its immediate surroundings and the larger context of New York City, a “garden” is introduced in the middle of the building, providing the nature this site lacks according to Dewey’s vision (Fig.2). The cafeteria is located adjacent to the garden, as “all the materials that come into the kitchen had their origins in the country served to unite the kitchen and dining room with nature.”6 The art and music rooms are also placed on the first floor, united together with the cafeteria and garden by the library, where “it symbolizes the relationship of practice to theory”7 (Fig.1).

The first to eighth grade classrooms are on top of the library, creating a vertical pillar of learning and playing built on research and knowledge. The grade classrooms on the second and third level connects to the kindergarten and special education and science rooms respectively, while maintaining contact with the central garden-atrium. The administration cluster is adjacent to the kindergarten, providing easy access to parents and is directly beneath the assembly hall, where it can easily communicate with the student body. The last volume on the top floor features a lounge that overlooks the 125 St. station. It also provides equipment storage to the rooftop playground that is on top of the learning clusters.

The first to eighth grade classrooms are on top of the library, creating a vertical pillar of learning and playing built on research and knowledge. The grade classrooms on the second and third level connects to the kindergarten and special education and science rooms respectively, while maintaining contact with the central garden-atrium. The administration cluster is adjacent to the kindergarten, providing easy access to parents and is directly beneath the assembly hall, where it can easily communicate with the student body. The last volume on the top floor features a lounge that overlooks the 125 St. station. It also provides equipment storage to the rooftop playground that is on top of the learning clusters.

︎Massing Strategies

︎Step 1+2: Program Distribution & Site Subdivision

︎Step 2-4: Minigame: Make your own program and massing!

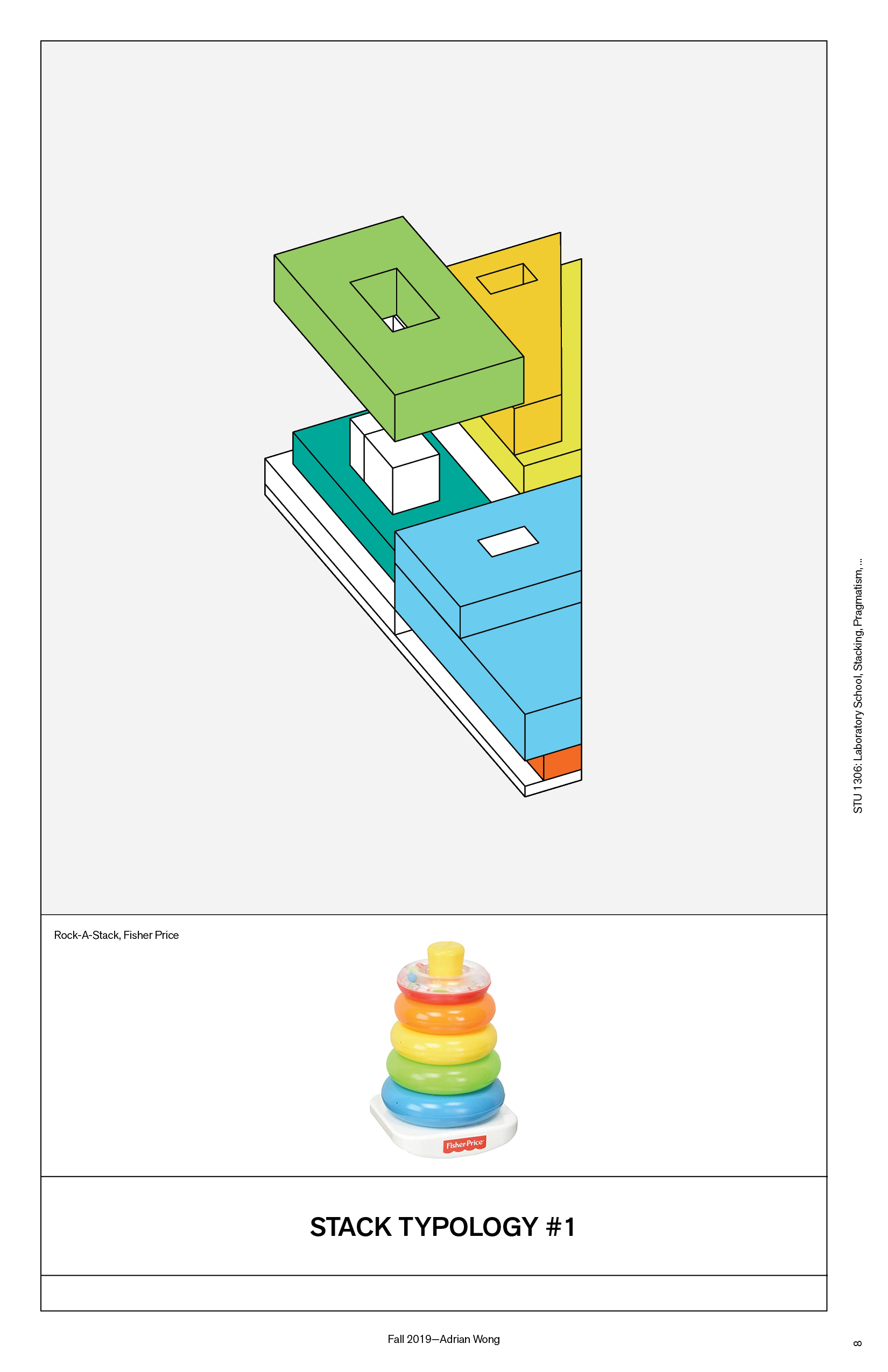

︎Stacking and Pragmatism

Pragmatism measures the truth of an idea by experimentation and by examining its practical outcome. The pragmatists rejected the idea of an absolute, and maintained that all principles be regarded as working hypotheses based on lived experience. In this line of thinking—stacking—in the built context of New York City, is a result of practical utilization and adequate allocation of limited resources and space. In his well-regarded conceptualization of stacking, Rem Koolhaus argues the heterogeneous section of the downtown athletic club represents the betterment of society as it draws from the collective identity of the metropolis. Pragmatism, similarly, draws from the North American mindset of “getting things done” to establish that practicality or real-world implementation should be considered in the formation and advancement of ideas. William James, a pragmatist predecessor of Dewey’s, explains how pragmatism can provide real approaches to ideas that seem impenetrable, since "new truth is always a go-between, a smoother-over of transitions".8

Pragmatism measures the truth of an idea by experimentation and by examining its practical outcome. The pragmatists rejected the idea of an absolute, and maintained that all principles be regarded as working hypotheses based on lived experience. In this line of thinking—stacking—in the built context of New York City, is a result of practical utilization and adequate allocation of limited resources and space. In his well-regarded conceptualization of stacking, Rem Koolhaus argues the heterogeneous section of the downtown athletic club represents the betterment of society as it draws from the collective identity of the metropolis. Pragmatism, similarly, draws from the North American mindset of “getting things done” to establish that practicality or real-world implementation should be considered in the formation and advancement of ideas. William James, a pragmatist predecessor of Dewey’s, explains how pragmatism can provide real approaches to ideas that seem impenetrable, since "new truth is always a go-between, a smoother-over of transitions".8

“There were 200,000 horses that pulled carriages in New York City, producing nearly 2,300 tons of manure daily. It accumulated in the streets and was swept to the sides like snow. The stench was so strong that urbanites welcomed motor vehicles as a profound relief, in addition to other methods to promote more effective sanitation practices.”9

—New York Times

C.B.J. Snyder’s H-type school breaks the conventional model of a suburban, horizontal-spread school, and produced an unlikely result that tackled the health problems of New York City by introducing a building typology that both symbolized progress through technology and education reform. In Synder’s case, stacking originated out of practical needs. Charles Sanders Pierce, a pragmatist alongside James, goes on to state that "consider the practical effects of the objects of your conception. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object."10

—New York Times

C.B.J. Snyder’s H-type school breaks the conventional model of a suburban, horizontal-spread school, and produced an unlikely result that tackled the health problems of New York City by introducing a building typology that both symbolized progress through technology and education reform. In Synder’s case, stacking originated out of practical needs. Charles Sanders Pierce, a pragmatist alongside James, goes on to state that "consider the practical effects of the objects of your conception. Then, your conception of those effects is the whole of your conception of the object."10

Hygiene and sanitation can be considered a practical effect, in the case of the H-typology, from the conception of stacking.The wide courtyard facing the street allowed for an internal courtyard that provided light and air, which worked well with limiting the size of the floors and aligning them vertically. The stacking of classrooms created a school environment with better hygiene and organization. This research led to Snyder’s specification and standardization of the five key elements for the school: large windows, central heating, indoor plumbing, fireproof materials and fire escapes. In the case of the H-typology, there is an alignment of practicality and aesthetics.

Final Dollhouse Model, 1/8” scale. This model is made with the intention that it is 1. a representation of architectural ideas and 2. a planning apparatus of spatial organization for the kids and teachers that occupy it.